Big Water, a Blue Whale, and a Sad Discovery

Expedition 2023: Delivering Sailing Vessel Resilience to her New Home

For 2 weeks, Jim, Brendan, and Corwin (4th person in photo is Brendan’s brother Kevin) were geared up to deliver our sailboat Resilience from San Francisco Bay partway to her new home in Puget Sound, WA.

Traveling north along this stretch of coast is notoriously tough, because prevailing winds and swells come from the north.

The team had to wait out days of gale-force winds with 7-9 foot seas, but heroically squeezed in 3 transit days. Between Point Reyes and Bodega Bay, however, our auto-pilot broke.

From Bodega to Fort Bragg, Jim, Brendan, and Corwin took turns at the helm.

Hand steering in rough conditions is exhausting, but there are other reasons cruisers value their auto pilot more than an extra crew member: They work hard 24/7, don’t complain, and they never get sea sick.

Thank you, Brendan and Corwin for helping us get Resilience closer to home!

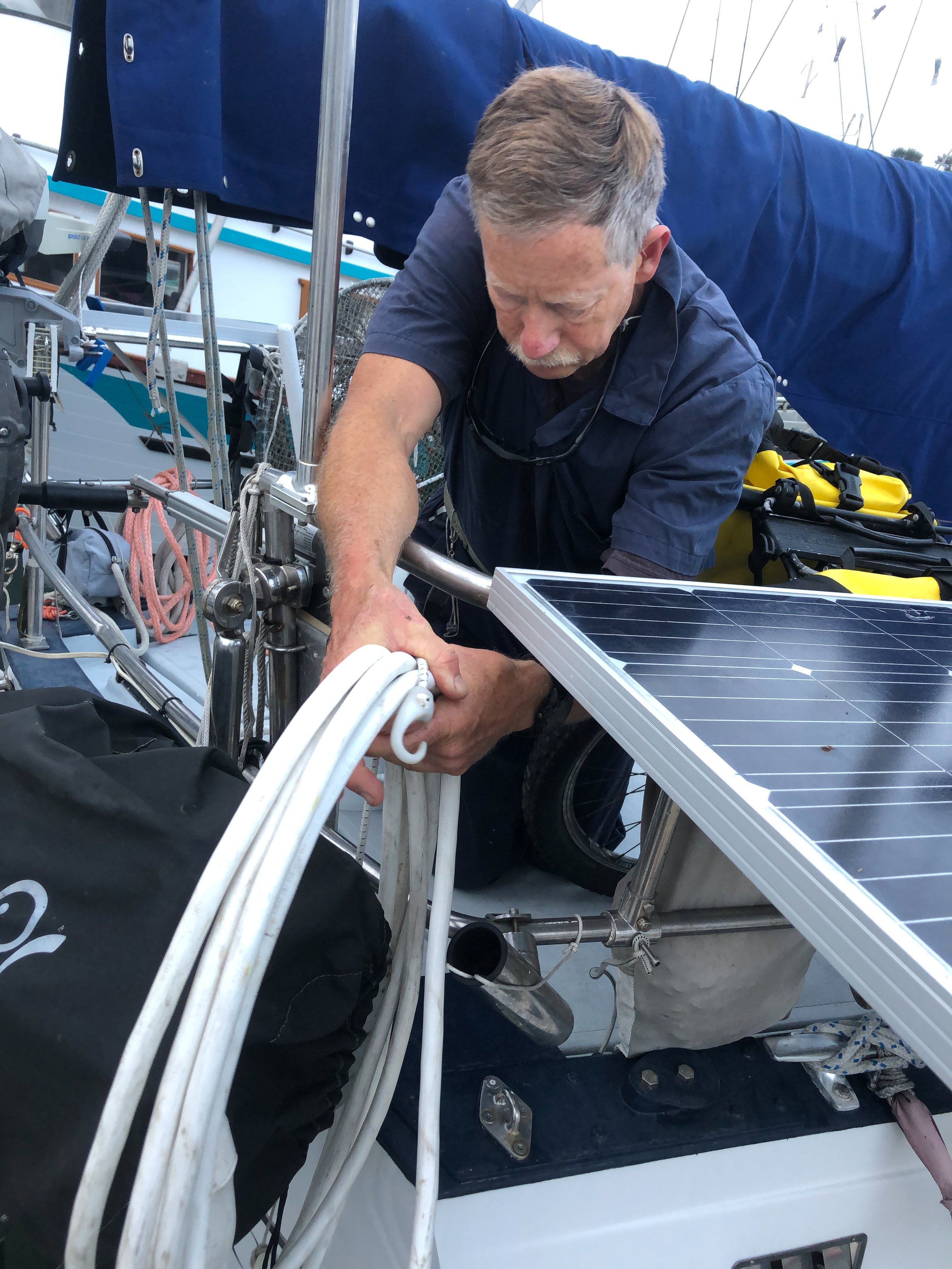

On June 23, I joined Jim as he was finishing two crucial projects—repairing the auto pilot and replacing the rudder post stuffing box (harder than it sounds). These jobs consumed 40+ hours, including diagnosis, locating oddball parts in a small town on a bike, and working in a tight space—what Jim calls yoga mechanics.

Before heading offshore, there’s alway lots to do. Here’s a sample from Fort Bragg:

1) Jim finishes the rudder post stuffing box repair (Hooray!).

2) Stow gear on deck including bikes and 3) the power cord used at the dock.

Down below, we: 4) fold up the dining table and use its special underside with edges to secure items. 5) Pull out and tie up the lee cloth on the settee, where we take turns resting in heavy seas. *The fabric “wall” prevents us from being tossed onto the floor by a big roller), and 6) secure cutting boards, wine glasses, books, etc.),

June 28 Weather Prediction: 15 Knot winds, 5 to 6 foot seas.

6:20 AM departure from Fort Bragg heading for Shelter Cove.

Leg 1 for me, 4 overall: Motoring from Fort Bragg to Shelter Cove through 5-foot swells was my shakedown passage. It was rough enough I almost got sick, which is rare. Staying on deck, eyes on the horizon--and spotting a humpback whale a mile away--helped fend off that awful feeling.

Once anchored in Shelter Cove, the wrap-around NW swell was enough that Jim launched "flopper stoppers" he'd fabricated when we were in Mexico. He adds a weight to one corner of each aluminum triangle. When submerged on a line from the boom, they dive and flatten with each wave, dampening the boat's motion. What a relief!

Getting a good night’s sleep our here is a safety factor.

Day 2 (June 28, Wednesday) loomed with a forecast similar to the previous day, but with worse conditions off of Cape Mendocino (as is often the case), and we debated whether to go. Windy.com informed us that sea state and wind would both be higher on Friday, so we pulled anchor to take advantage of the 2-day window.

We motored out into fog and 5 to 6-foot swells. Resilience, a Contest 42 built in Holland, is a sturdy cruising vessel designed for offshore sailing. But even she took a handful of steep waves over her bow—something that rarely happens.

Whale Encounter

Two hours out, while Jim rested on the settee down below, I spotted a blow ahead. Wow, I thought, that looks taller than a humpback whale’s blow—the more common species in these waters.

“Hey, Jim. Sorry to wake you, but we’ve got a blue whale ahead.” In seconds, he was up top.

The whale happened to be close enough we could get photo IDs by slowing down and not deviating much from our track line. With the rough conditions, we couldn’t afford to linger longer than one surfacing-dive sequence.

When our boat is pitching or rolling a lot, I clip my harness to the dodger or elsewhere so I can lean back and pivot with hands free to hold my camera. (Photo taken at a different time.)

I’m a volunteer contributor to a longterm study of whale populations led by Dr. John Calambokidis. When encounters like this happen, I take photographs used to identify individual whales for population and movement studies and send them to the Cascadia Research Collective, Dr. Calambokidis’s group,

By the way, boaters not operating under a research permit are required to stay at least 100 yards from whales. The images below were taken closer than that—and also with a long lens and then cropped.

Blue whales are identified by the shape of their dorsal fins but mainly by the blotches of light and dark pigment on their sides. Pigment patches remain stable over the life of the whale, whereas scars accumulate over time.

The 9+ pock-mark scars visible on this blue whale’s left flank are likely where they were bitten by a cookie-cutter shark, also known as the “demon whale-biter.”

Hearing the powerful exhalation-inhalation cycles of a member of the largest animal species to ever have lived on the planet filled me with awe. While concentrating on taking useful photos from our pitching boat, that emotion suddenly twisted to sorrow when she (gender not known; pronoun randomly chosen) dove—revealing the V-shaped gash in her tail stock.

It dawned on me then that the whale’s swimming behavior had also been peculiar—more sinuous like a snake—compared to other blue whales I’ve observed. An injury like this was probably due to being hit by a ship’s propellor or entanglement in fishing gear. If I learn more about this whale’s history, I’ll pass it on.

Ship strikes and gear entanglement are an increasing cause of death for many species of large whales, but witnessing this injured blue whale was different from reading about impacts on their populations. It troubled me to think of the months when the wound was fresh, and how the damage now altered how the whale swam. And what about the pain? How do whales, and other mammals for that matter, perceive and cope with that?

Research to reduce collisions between whales and large cargo ships are ongoing. In one study entitled, “Simultaneous tracking of blue whales and large ships demonstrates limited behavioral responses for avoiding collision” led by Megan McKenna (2015), tagged blue whales which had a ship cross their path, responded with a slight increase in the slope of their dives. But they did not seem to have the ability to alter their horizontal direction, that is, to turn to the left or right to avoid a collision.

Cape Mendocino to Eureka, CA

By mid-morning, we'd adjusted to 6-foot swells. While rounding Cape Mendocino, however, and only 10 minutes after leaving the whale, the wind on our nose kicked up from almost none to 20-25 knots, and we took a few more waves over the bow. (Video from then posted on Facebook and Instagram.)

The way the Cape protrudes west accelerates the wind, which fuels the waves. And yes—there were moments at the mercy of powerful seas, wind thrumming the rigging, when we glanced at each other with grim expressions.

After so much rough water and photographing the whale, I took a break to rest in the aft cabin.

The 10-hour day wore us out, but Reslience pressed on and Jim's 2 major repairs held solid. At 5:00 PM, we tied off at a dock in Eureka, CA and got dinner started. It’s odd how, after a tough passage, the elation of reaching a safe harbor blurs your recollection of concerning moments offshore.

We did it! We got our boat up the coast another notch—and around our nemesis—Cape Mendocino.

Thank you everyone who has posted a review at Amazon and GoodReads. For unknown, debut authors, reader reviews and ratings make a big difference.

Available at bookstores, libraries, and online.

BOOK CLUBS: To receive a Book Club Organizer Packet or schedule a Live Virtual Author Discussion, email me at info@bethannmathews.com

Wishing you good health and well being!

Beth

P.S. Was this email forwarded to you? If so, subscribe here to receive photo essays like this in the future.